News from our seed laboratory

It is a pleasure to work in a forest seed laboratory immersed in the full nature of the Alpujarra in Spain. With so much attention focused on forest seeds and their possibilities for reforestation, the Alpujarra offers us a scenario where to observe when and where seeds are born, how plant communities are established, diverse forms of natural regeneration, etc. It is a paradise for the task of developing a methodology of direct forest sowing, which breaks with the established canons, and that needs to be built more from direct experience with nature than from a set of theories about what nature is.

This is not to say that we do not use science. But science is most useful when it has its place and does not occupy everything, when the scientist recognizes himself humble in the face of the mystery of nature, and science goes from being a generator of truths to being a tool to deepen the truth.

This month the lab has gotten up and running again after the move with different trials with the seeds. The main objectives of these trials are to better understand the germinative processes of the species we will sow this fall, to find priming treatments for those species and to refine the formula of the ingredients of the seed balls that the drone will launch.

Before looking for a priming treatment for a species, we must know very well its latencies and its standard germination process. Standard germination is the process that seeds are commonly thought to do to germinate: the seeds are moistened and this moisture is maintained for days or months (with or without temperature changes depending on the species), until the root emerges. This definition of germination does not take into account that seeds can dry in the middle of that process, maintaining and even improving their viability (priming). When we subject seeds to hydration/drying cycles, we are germinating the seeds in a very different way than a farmer has ever done, but much like how seeds actually germinate in nature.

We have started the investigation of different forms of standard germination in: mastic, aladierno, hawthorn, labiérnago, barberry, palmito, cornicabra, hawthorn, cherry blossom and several shrub legumes.

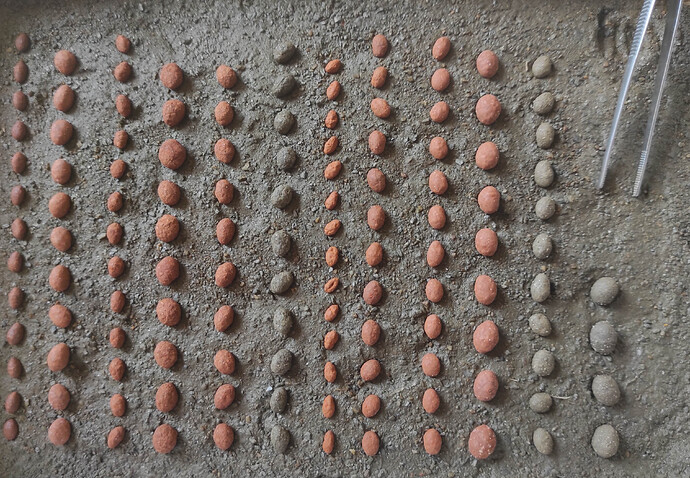

Seedballs

With regard to seed balls, we have started the introduction of repellents into the ball. Some balls are made with cayenne powder to provoke the aversion of mice. Others contain albarrana onion powder, for the same purpose. To those ingredients we have also joined a visual camouflage system, the last layer of the ball is earth from the same place where they will be planted. We are testing whether these materials inhibit germination and preparing the field test to see how mice react.

Episode 3 of reforestation podcast: Seeds and Drones

The Seeds and Drones program 3 is now available. In this episode we spoke with Dani Calatayud, Lot Amorós, Sergio Pérez, Borja Terán and Andreu Ibáñez, about the different novelties that have occurred in recent weeks in the project, with the majority of the team in the Pitres facilities in the Alpujarra.

Reforestation Assistant and Simulator

Together with @liquidgalaxy this year we mentor Karine Pistili, a Computer Engineering student from Brazil who will develop an app we have designed, called RAS: Reforestation Assistant & Simulator.

This application will help in the management of reforestation projects, with use cases for landowners, forest engineers and drone pilots.

Stay tuned, we’ll launch it later this summer. Thank you to #GoogleSummerofCode for giving us this opportunity to expand our reforestation methodology around the world.

Field counts

This month we have also finished the plant count of the seeds we sown this fall in Sierra Lújar. Of the three species that we wanted to monitor their results, in two of them (halepensis pine and juniperus phoenicea) we had errors in the elaboration of the priming treatment in the laboratory. The sowings we did with these “non-optimal priming” treatments of Bolina (Genista umbellata) were not satisfactory. We have obtained interesting data and results (sowing at the end of November of seeds with / without priming and sown with / without nurse):

- The seeds with priming treatment germinated immediately after the first rain and as of May were very developed. On the other hand, the seeds without priming germinated during the spring and in May they were very small.

- In May, the survival rate in the places with 1 or 2 plants has been: 70% in seeds with priming and 23% in seeds without priming.

- Given the little development of the unprimed plants, they are expected to succumb during the long summer.

- The losses by wild boars were significant in the sowings without nurse. When the plant grows next to the trunk of another shrub it is much more protected and the wild boars do not like to lift soil strongly caught by roots of woody shrubs.

- The seeds germinated well without a nurse (and then destroyed by wild boars). Several factors influenced this: the planting areas are the north face of Lújar, so there is little sunshine; the first rain after planting was abundant; low temperatures in December favored slow desiccation. Although the nurse did not influence germination, it did influence protection against wild boars.

Want to learn how to priming with forest seeds?

Access the Seedlings course where we make an introduction to the techniques of improvement of seeds with priming:

https://www.aguabosque.com/entiende-tus-semillas/

Mycorrhization of seeds

Although we have not been able to test the optimal treatment of priming in the field for the halepensis pine, we will be able to observe the differences in the pines sowed with / without spores of ectomycorrhizals. We believe that the planting area has sufficient ectomycorrhizal inoculum through the cistus clusii shrub and we will check if the pioneer mycorrhiza (Pisolithus Tinctorius) that we introduced improves the establishment.

To finish the news of May, we have to remember the visit of Ignacio, Angel and Christine (and their truffle dogs). Christine has been supporting the project for a year with her knowledge of mycorrhizal fungi. This time he came with two friends to search with their dogs for what species of truffles still exist in the well-formed forests of Sierra Lújar. Each truffle is actually billions of spores in a fruiting body. We use these spores to inoculate quercus. We wanted to see if it would be profitable to collect native truffles for use in reforestations. The answer was no. The truffles in Lújar are very small, due to the low rainfall, so we will continue to look for truffles in other places to support the reforestation of Sierra Lújar.

Continuity of monthly news

It takes us a long time to collect for you this monthly news, we make them available every month in Spanish and English. On the other hand, we are not sure of its usefulness to the people who read them, sometimes it can be technical information that may interest another type of public, so we are considering sharing the information in other ways that can be more efficient for everyone.

Our goal is to be able to develop and share a large-scale reforestation methodology and to be able to share it for free with the world. For this we need your help, to finance development through our Patreon.

Have you come this far? Please tell us in the comments what interests you and how you think we could improve and make sustainable this open development. Thank you!